No Place for Idle Hands-Part 2

The difference between the work of women and men in Irish workhouses

- · Embroidery

- · Knitting

- · Making socks, shawls, handkerchiefs & other items of clothing

- · Lace-making

- · Crochet

- · Quilting

- · Netting

- · Flowering & Sprigging

The above list shows the variety of skilled needle-work

performed by female paupers. Note the

inclusion of a type of needlework which is largely forgotten today; flowering and sprigging. This entails the

embroidering of muslin with small sprays of foliage or floral patterns.

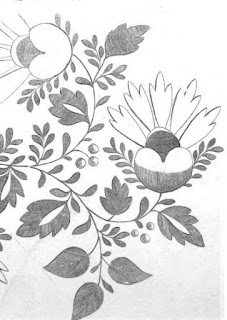

Many different patterns could be used and were widely circulated in periodicals. In an era before the ready availability of printed fabric, a huge volume of labour was required to supply the demand for this kind of needlework. Below we can see a popular muslin pattern from R. Ackerman's Repository of Fashions 1829, which shows a fashionable flowering/sprigging design.

Many different patterns could be used and were widely circulated in periodicals. In an era before the ready availability of printed fabric, a huge volume of labour was required to supply the demand for this kind of needlework. Below we can see a popular muslin pattern from R. Ackerman's Repository of Fashions 1829, which shows a fashionable flowering/sprigging design.

Men were engaged in a different selection of industrial activity. 125 out of 163 workhouses (just over 75%) provided their

young male paupers with some sort of industrial training. The skills that were

taught included agriculture, shoe-making, tailoring, weaving, baking, carpentry

and tin-smithing.

In the 1852 Return to Parliament which lists the kinds of

employment at all 163 workhouses, we see that 89 Unions made their own shoes,

which appears to be one of the most common skilled jobs given to male paupers.

Strabane even had extra to sell!

There are also numerous mentions of weaving and

carpentry, with several entries for smithing of some kind, such as tin-ware

making, and nail-making. Even coopering (barrel making) is mentioned in several

workhouses. However, much of this labour was

simply to supply workhouse demand rather than for sale to outside

parties.

By

1852, most workhouses were keeping down

food costs by growing their own crops. In figures from that year we can see

that 137 workhouses engaged in crop cultivation, growing produce such as oats,

barley, cabbage, parsnips, mangel-wurzel (a type of giant beet), onions, wheat,

corn, green-crops, and potatoes.

There were even model farms at Rathkeale and Carrick-on-Suir workhouses in Co. Limerick. In fact, 57 of the 137 farming workhouses had surplus produce which they sold and 50 workhouses employed an Agriculturist to teach farming to workhouse boys as part of their industrial training.

There were even model farms at Rathkeale and Carrick-on-Suir workhouses in Co. Limerick. In fact, 57 of the 137 farming workhouses had surplus produce which they sold and 50 workhouses employed an Agriculturist to teach farming to workhouse boys as part of their industrial training.

Despite political views to the contrary, Irish paupers could be highly skilled craftspeople,

readily taught students and diligent workers, a fact which is often overlooked

in the story of Irish workhouses. Despite the fact that parliamentary

legislation strove to curtail all skilled activities in Irish workhouses,

inmates produced goods which were sold to private individuals, at markets, at

auction and shipped overseas to 'Belgium,

Germany and France' (The Nation Newspaper, 1853).

Some

workhouses even filled contracts for manufacture, sending embroidery, textiles

and clothing to suppliers. These items were light weight and easy to transport

which is perhaps why they outnumber other types of crafts when it comes to

commercial interest.

Another factor may simply be that needle-work was largely a female task at this time, and there were significantly higher numbers of able-bodied women compared to men in the workhouses. In 1852 there were more than double the number of able-bodied women to men in Irish workhouses.

Another factor may simply be that needle-work was largely a female task at this time, and there were significantly higher numbers of able-bodied women compared to men in the workhouses. In 1852 there were more than double the number of able-bodied women to men in Irish workhouses.

All of Ireland

Total Able-bodied Males: 19,353

All of Ireland Total Able-bodied Females: 45,814

As new research sheds light on the skilled crafts which

were carried out in Irish workhouses, we need to realise that perhaps life was

more varied in these institutions than the Poor Law legislation would have us

believe. Certainly, there is a wealth of manufacture that has been completely

unacknowledged which is a great shame.

We will never look back with fondness on the

workhouse system, but never the less, it's important to recognise the

ingenuity, skill and determination of its inmates. Our next big question is

whether any of the baskets, floor mats, shirts, embroidery or pieces of fine

lace have survived, or are the products of these 'Houses of Industry' lost to

us forever.

By Elizabeth Carter

Comments

Post a Comment